If you have never been rockpooling at night, then you’re missing out. It is definitely something that should go on your list of post-lockdown activities. I discovered the excitement of nocturnal seashore wanderings a few years ago when attempting to record the rasping sounds of grazing limpets on our local beach. Where I live they are most active during low tide at night. Having successfully completed the task I did a quick tour of the rock pools to see what other creatures were out and about and was blown away.

Obviously safety is very important, so lets get that in here at the start. You do, of course, need a bright torch, preferably a head torch which leaves your hands free to help with balance and scrambling around on wet, slippery rocks in the dark. Preparations must include checking tide times, letting someone know where you are and making sure you have a bright light to aim towards to find your way off the beach.

We also take a bat detector (to listen for bats feasting on seaweed flies and other flying insects along the beach strandline) and a UV-light (black light). My favourite thing on our night-time rock pool rambles is to look for animals that fluoresce. When you shine your UV torch on them they glow in the most amazing colours – neon orange and unearthly green.

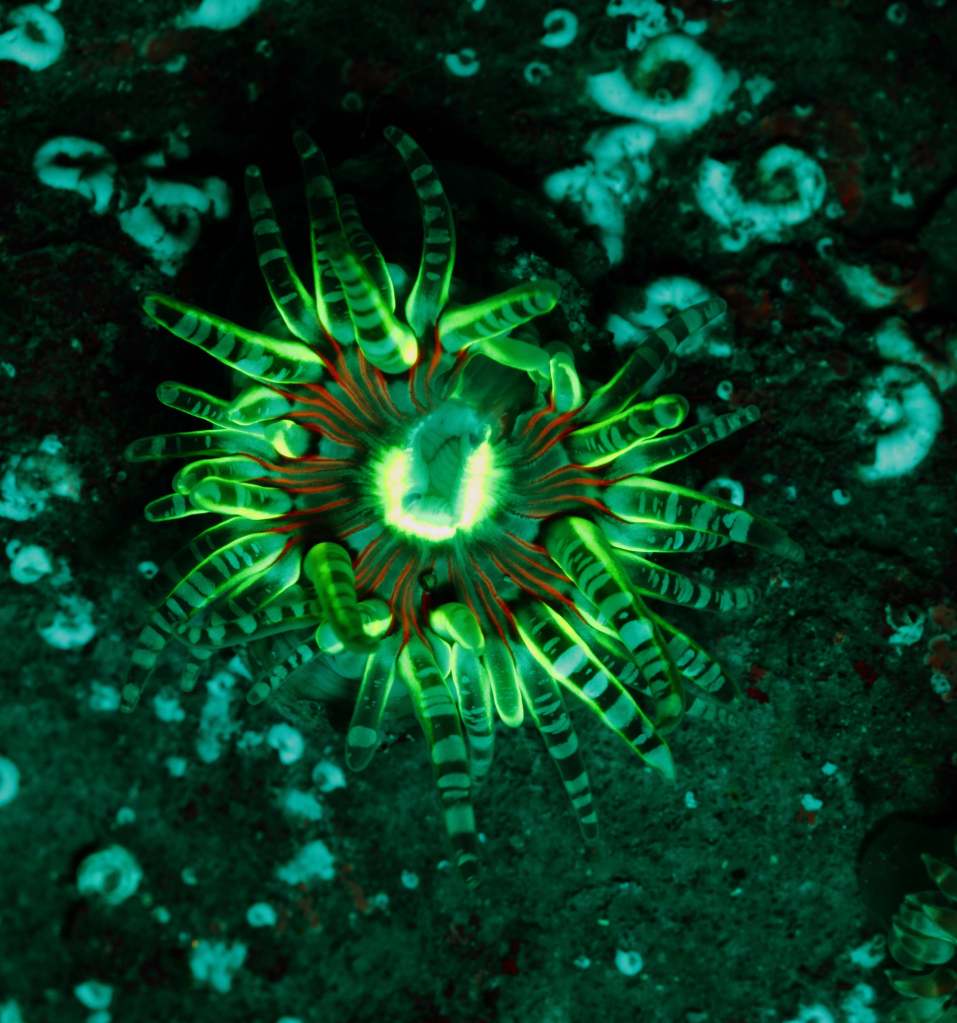

Perhaps the easiest to spot are the sea anemones. Of the species found on the seashore, nearly all seem to fluoresce. The brightest ones are the Snakelocks anemones, although only the green variety do this. They can look very eerie as your UV torch sweeps across a rock pool and reveals a tangled mess of long writhing tentacles glowing ghostly green in the dark. Gem anemones, Daisy anemones and Strawberry anemones also put on a good light show.

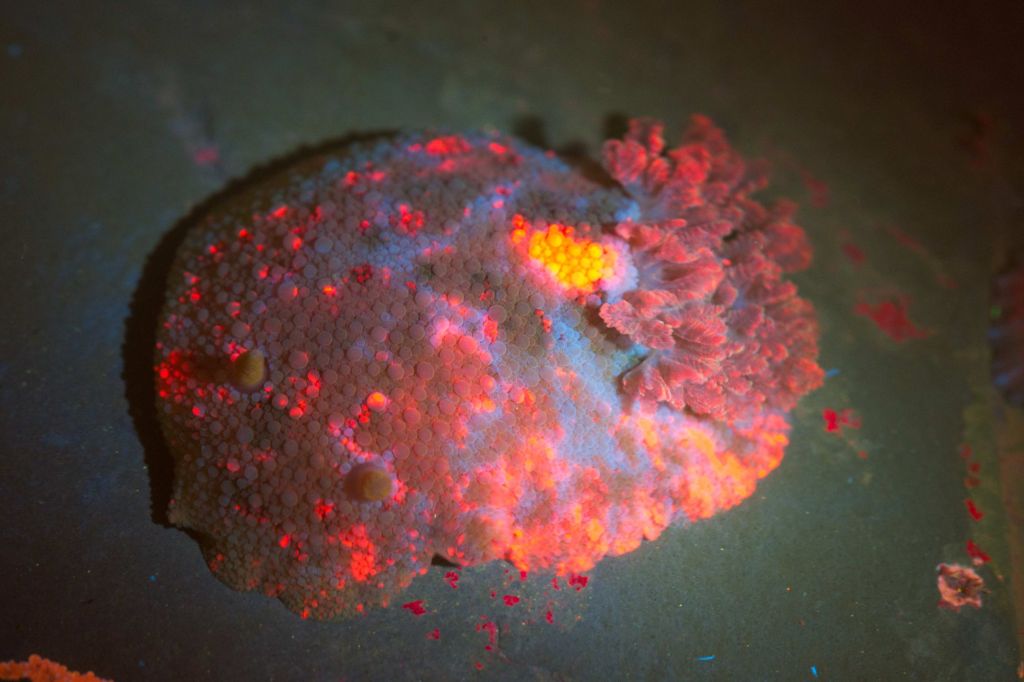

We have found that some sea slugs also fluoresce. On a recent nocturnal ramble, one of our party spotted a Sea lemon. Not expecting much we turned the UV-light on it and the neon orange colours leapt out at us! The mottled colours of the animal were picked out, some glowing and others muted. Why would some parts react to the light and not others?

Seashore animals ranging from Lightbulb seasquirts to sea spiders and cup corals fluoresce but it seems to be a bit random. What they have in common is the presence of a protein which absorbs UV light and converts it into a less harmful wavelength in the visible light spectrum. Green Fluorescing Protein emits green light, but others can emit orange, red, pink or yellow light. It is thought that some seashore species might use it as a kind of sunscreen, to protect them from the very damaging UV light they are exposed to every day. For animals in deeper water, presumably there are other advantages to be gained, or perhaps it’s presence gives them no evolutionary advantage at all and is just accidental.

Some elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) are known to use fluorescence, possibly as a way of finding each other in the ocean, as UV light penetrates deeper into the water than other wavelengths. When we had the opportunity to try it out on a newly hatched baby spotted ray in our aquarium, prior to release, we couldn’t resist. Sure enough the little ray glowed like a firework!

As well as the seashore light-show, a nocturnal ramble can reveal a hive of crabby activity. Shore crabs are everywhere, scrambling through rock pools clambering over stones and seaweed, and adventuring over the sand. We have even found them climbing up the cliffs, where fresh water oozes from the rock and gives rise to curtains of green algae. When they stumble across a rival they stop to have a sword fight, using sharp claws as weapons to overpower their opponent.

I love the Sea slaters, large relatives of woodlice, scurrying around the seashore at lightening speed, like tiny mice on a mission. Under cover of darkness they dash around scavenging on rotting seaweed and other unmentionable detritus. They are air-breathers so must find an air-pocket under a stone or retreat to crevices in the cliffs and rocks above high tide mark before the tide comes in.

On the upper shore, we have spotted the odd mammal too. A field vole was so busy munching on seaweed flies on the strandline that it didn’t bat an eyelid when our head-torch beam picked it out in the dark. Another time a fox was lurking beneath the cliffs at the back of the beach, obviously on the look out for voles, mice, shrews, rats and any other small mammal that regularly visits the beach at night. Although I haven’t seen one myself, I’ve heard that hedgehogs frequent some beaches, grubbing about amongst the line of rotting seaweed and carcasses thrown up by the tide. I have even heard that they may feed on the odd whale carcass that washes ashore! The strandline can be a bountiful place for wild animals.

Further down on the shore, I love crouching low in between the boulders on a calm, quiet night and listening for the scrapings of molluscs. Limpets make the loudest sound as they scratch their rasping tongues across rocks, scouring the film of seaweed spores and leaving a zigzag trail behind. Turn your sound on and click here to hear them. Topshells make a softer sound but if it’s quiet enough you will hear them too.

Going for a nocturnal beach wander makes me feel like I did as a kid when I was allowed to stay up after dark and go outside, armed with blankets and torches, to listen for owls and badgers. There is something ceaselessly exciting about being in the countryside (or coast) at night, away from all the daytime noise, hustle and bustle, with the secretive rustlings and scrapings of unknown creatures hidden from view. With such a wealth of intertidal activity, I can’t wait to get back out for a night-time rummage among the rock pools. When will this lockdown ever end?

I shall have to give this a go , thank you for posting , cheers Craig

LikeLike

Definitely worth it. Just be extra extra careful and stay safe.

LikeLike